In the last three months, I have done more video post-production than I have done in the past 12 years. Surprisingly, in these years, nothing seems to have changed. Considering how much media is now machine analyzable content, such as audio and visual, I’m surprised there aren’t more patterns that make navigating and arranging video content faster. Beyond that, I’m surprised there isn’t more process for programmatically composing video in a polished complimentary way to the existing manual methods of arranging.

In 1918, when the video camera was created, if you filmed something and wanted to edit it, you took your footage, cut it and arranged it according to how you wanted it to look. Today, if you want to edit a video, you have to import the source assets into a specialty program (such as Adobe Premiere), and then manually view each item to watch/listen for the portion that you want. Once you have the sections of each imported asset, you have to manually arrange each item on a timeline. Of course a ton has changed, but the general workflow feels the same.

How did video production and editing not get its digital-first methods of creation? Computing power has skyrocketed. Access to storage is generally infinite. And our computers are networked around the world. How is it that the workflow of import, edit, and export take so long?

The consumerization of video editing has simplified certain elements by abstracting away seemingly important but complicated components, such as the linearity of time. Things like Tiktok seem to be the most dramatic shift in video creation, in that the workflow shifts from immediate review and reshooting of video. Over the years, the iMovies and such have moved timelines, from horizontal representation of elapsed time into general blocks of “scenes” or clips. The simplification through abstraction is important for the general consumer, but reduces the attention to detail. This creates an aesthetic of its own, which seems to be the result of the changing of tools.

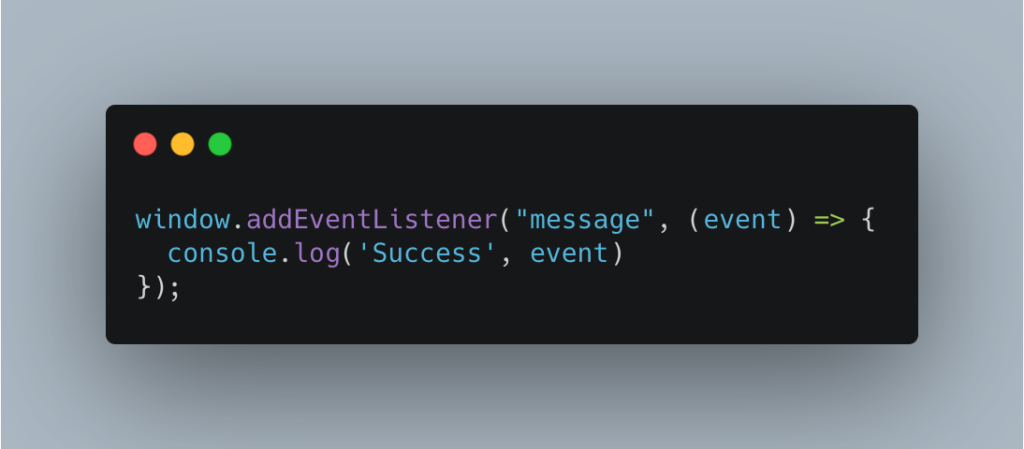

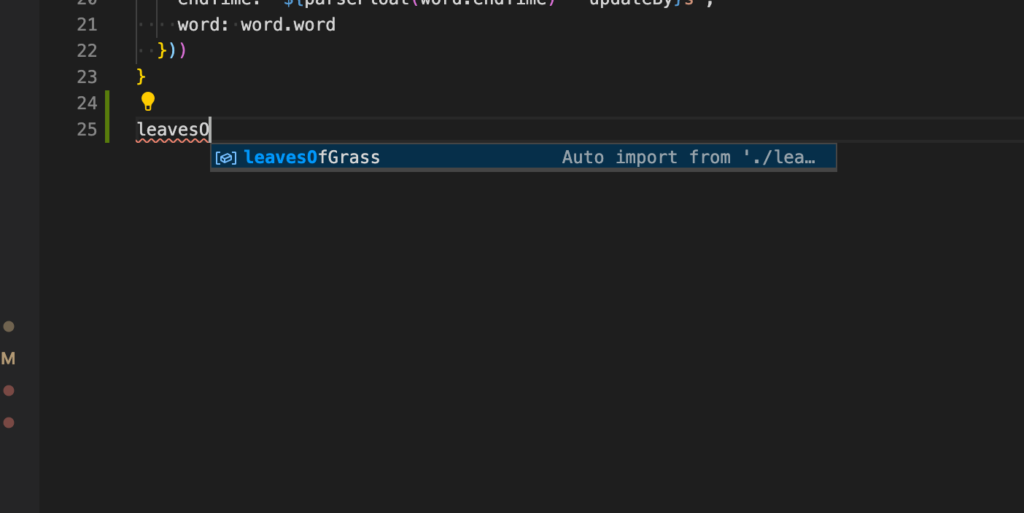

Where are all the things I take for granted in developer tools, like autocomplete or class-method search, in the video equivalent? What is autocomplete look like in editing a video clip? Where are the repeatable “patterns” I can write once, and reuse everywhere? Why does each item on a video canvas seem to live in isolation from one another, with no awareness of other elements or an ability to interact with each other?

As someone who studied film and animation exclusively for multiple years, I’m generally surprised that the overall ways of producing content are largely the same as they have been 10 years ago, but also seemingly for the past 100.

I understand that the areas of complexity have become more niche, such as in VFX or multi-media. I have no direct experience with any complicated 3D rendering and I haven’t tried any visual editing for non-traditional video displays, so its a stretch to say film hasn’t changed at all. I haven’t touched the surface in new video innovation, but all considering, I wish some basic things were much easier.

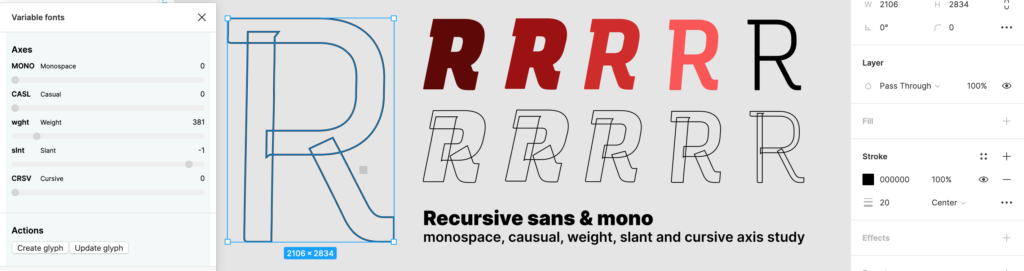

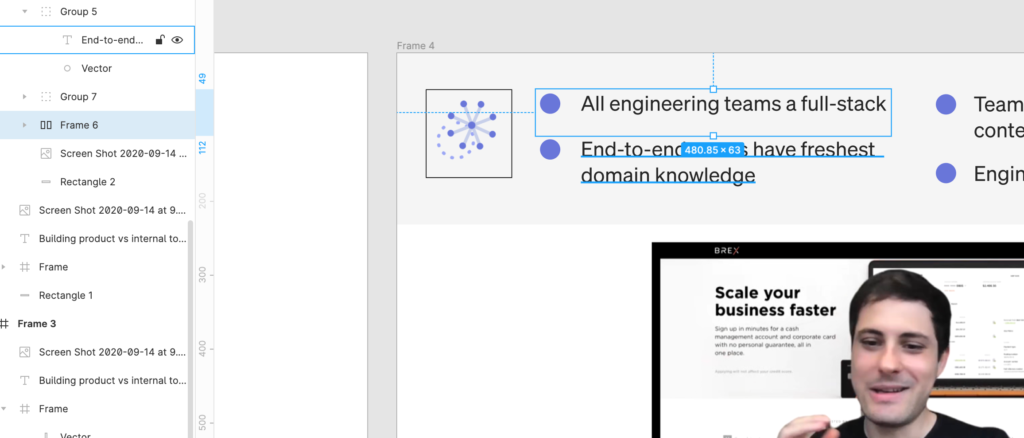

For one, when it comes to visual layout, I would love something like the Figma “autolayout” functionality. If I have multiple items in a canvas, I’d like them to self-arrange based on some kind of box model. There should be a way to assign the equivalent of styles as “classes”, such as with CSS, and multiple text elements should be able to inherit/share padding/margin definitions. Things like flexbox and relative/absolute positioning would make visual templates significantly much easier and faster for developing fresh video content.

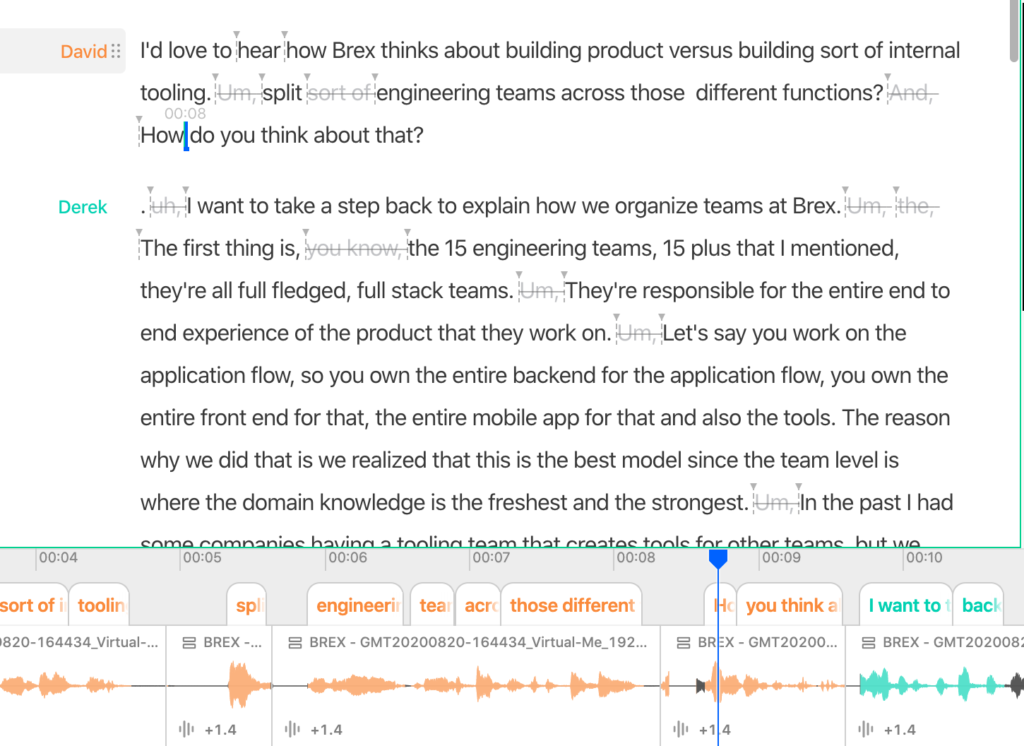

I would love to have a “smarter” timeline that can surface “cues” that I may want to hook into for visual changes. The cues could make use of machine analyzable features in the audio and video, based on features detected in the available content. This is filled with lots of hairy areas, and definitely sounds nicer than it might be in actuality. At a basic example, the timeline could look at audio or a transcript and know when a certain speaker is talking. There are already services, such as Descript, that make seamless use of speaker detection. That should find some expression in video editing software. Even if the software itself doesn’t detect this information, the metadata from other software should be made use of.

More advanced would be to know when certain exchanges between multiple people are a self-encompassed “point”. Identifying when a “exchange” takes place, or when a “question” is “answered”, would be useful for title slides or lower-thirds with complimentary text.

If there are multiple shots of the same take, it would be nice to have the clips note where the beginning and end based on lining up the audio. Reviewing content shouldn’t be done in a linear fashion if there are ways to distinguish content of video/audio clip and compare it to itself or other clips.

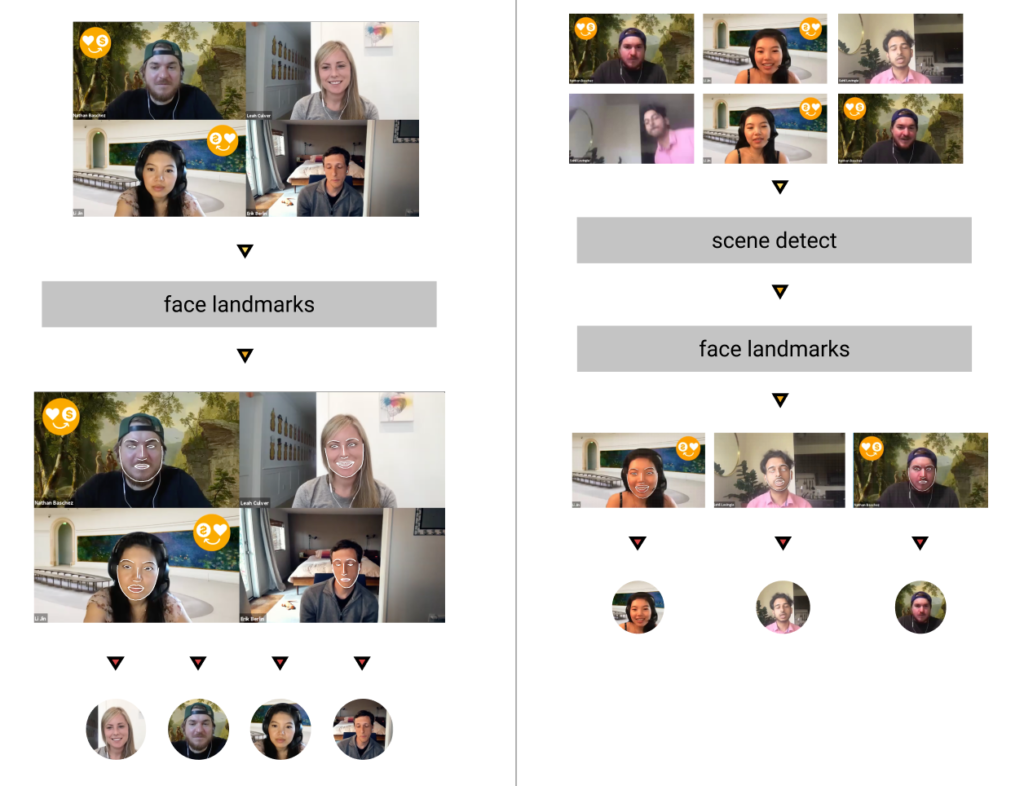

In line with “cues”, I would like to “search” my video in a much more comprehensive way. My iPhone photos app lets me search by faces or location. How about that in my video editor? All the video clips with a certain face or background?

Also, it would be nice to generate these “features” with some ease. I personally dont know what it would take to train a feature detector by viewing some parts of a clip, labeling it, and then using the labeled example to find the other instances of similar kinds of visual content. I do know its possible, and that would be very useful for speeding up the editing process.

In my use case, I’m seeing a lot of video recordings of Zoom calls or webinars. This is another example of video content that generally looks the “same” and could be analyzed for certain content types. I would be able to quickly navigate through clips if I could be able to filter video by when the video is a screen of many faces viewed at once, or when only one speaker is featured at a time.

All of this to say, there is a lot of gaps in the tools available at the moment.